[ad_1]

Britain is resetting its relationships with Africa and other countries in the Global South after more than a decade of neglect. At the United Nations in September, British Prime Minister Keir Starmer pledged that his government would:

Returning Britain to a position of responsible global leadership.

This should also include reconnecting with countries in the Global South who feel ignored and where Britain’s voice is currently diminished.

The new Labor government’s recent review of Britain’s global influence and international economic development policy provides an opportunity to reassess and restart these relationships. We must seize opportunities for the sake of world stability.

The post-Cold War order is fraying. The United States is increasingly reluctant to act as a global guarantor of a multilateral system that adheres to international rules and respects human rights and freedoms. China, Russia, and emerging middle powers such as Iran, Turkey, and the Gulf states seem content with a multipolar system based on the use of military and economic power. Meanwhile, the accelerating effects of climate change are increasing challenges to regional stability in Africa, Asia and the Middle East.

As a scholar and diplomat, I have been pursuing these questions for nearly 50 years. A lot has changed over the last few years, but recent UK governments have been slow to adapt to these changes. To reconnect with Africa and the countries of the Global South, Britain needs not only new policies but also new attitudes. And, perhaps paradoxically, the Commonwealth can play a constructive role in achieving this.

British problems

Preoccupied with domestic political and economic difficulties since leaving the EU, recent British governments have neglected both Africa and the Commonwealth.

Aid was cut and policy incoherence was further exacerbated by the merger of the Foreign and Commonwealth Office and the Department for International Development.

An investment conference with Africa scheduled for early 2024 was suddenly canceled.

Successive prime ministers have spent little time meeting with other leaders from Africa and the Global South. They were unable to answer questions asked about British-Southern relations.

However, the UK’s links with these countries remain strong. In particular, through the growing diaspora communities within the UK that are now an integral part of the UK’s social and political fabric. With 5.5 million people of Asian descent and 2.5 million people of African or mixed descent in the UK in 2021, we need to recognize these bonds politically.

Read more: How Commonwealth countries established a new way to appoint judges

Most of those Britons are from Commonwealth countries. The Commonwealth of Nations as an organization is no substitute for close engagement with each country. But it provides a forum where connections can be made and new, more equal relationships can be built.

The British government has ignored it, but King Charles, the ceremonial head of the Commonwealth, has not, as his 2023 visit to Kenya showed. And other countries are still looking to join, like Gabon and Togo last year.

federal government summit

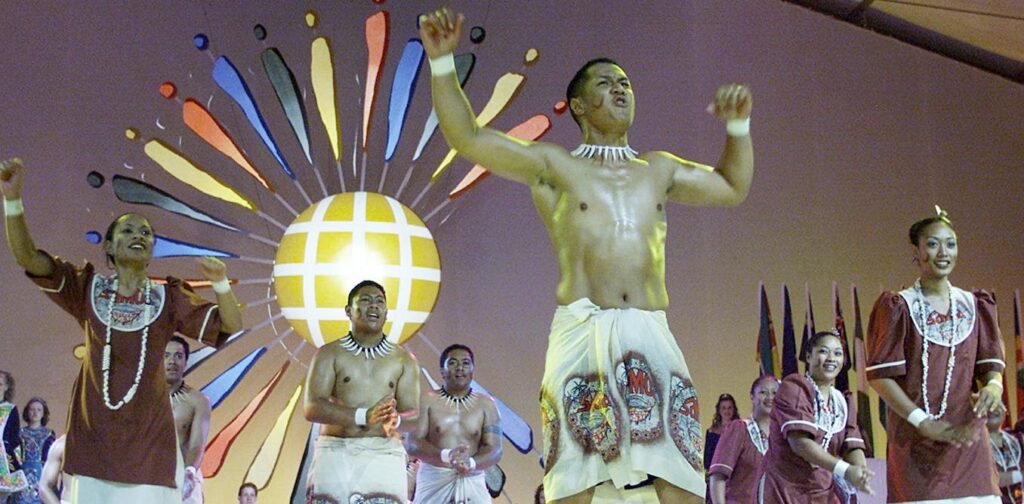

From October 21 to 26, Samoa will host the biennial Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting (Chogum), this time to elect a new African Secretary-General. The summit will include major greenhouse gas emitters, from the G7 members to the least developed countries, from the most populous (India with 1.45 billion people) to the smallest (Tuvalu with less than 10,000 people). It brings together representatives from every continent, from small islands at risk to small islands in crisis. It disappears into the ocean floor.

Despite its imperial origins, the Federation is an international network that cuts across multipolarity with the risk of dividing the world. This includes countries in the South, North, and East of the world. This diversity makes it an ideal forum for honest conversations about difficult issues such as climate change and multilateral reform.

Unlike the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (Focac), which was recently held in Beijing, the Federation is an organization run by its members. They share common values and interests, as well as a common language. They come together to exchange ideas, not promises of investment or aid. A tradition of democracy and equality among its members makes this organization unique and valuable. For example, it provides every member state with a ready-made network of global influence. For small island states, especially in the Caribbean and Pacific, it is one forum where their voices can be amplified.

This is important. Opportunities to build consensus are needed now more than ever as communities struggle to address global challenges of the scale of climate change and pandemics, or to resolve regional conflicts. Wars in Ukraine, the Middle East, the Sahel region, and the Horn of Africa are harbingers of what is to come if we fail to maintain a global structure that resolves these conflicts rather than exacerbating them. The UN’s peacebuilding efforts may then be successful, rather than futile and frustrated.

What Britain should do

Britain is just one voice among many, and we need a compelling narrative that helps maintain a world order that can meet humanity’s challenges, rather than one that simply fights over what’s left. The Commonwealth, like the United Nations, is where the UK can begin to build support for a more equal and more effective global system.

A new narrative, and a new relationship between Africa and the Global South, must be based on four elements:

First, repent of your past sins. The British Empire played a central role in shaping the modern world, for better or for worse. Better things are often taken for granted, but the sins of empire still reel and disrupt relationships like a stone in a shoe. So it’s best to acknowledge them and move on.

Second, new relationships must be based on mutual respect and partnership. In particular, the days of traditional development programs with paternalistic tendencies are over. Just as many feel countries in the Global South are gaining from China, what they need is a recognition of the whole relationship and a focus on the political and economic sources of growth. It is a true partnership of equals.

Third, the UK will work with African and other southern governments to increase its voice in multilateral institutions such as the United Nations and the International Financial Institutions, ensuring that these institutions truly protect their interests and that countries We need to protect that institution.

Finally, the UK needs to engage with the people of these countries as well as the governments of these countries. As the battle for narratives intensifies, the BBC World Service, British Council and the UK’s education sector are becoming more important in countering disinformation. Now is the time to strengthen them, not weaken them.

Having a new narrative along these lines in Chogum incorporated into the government review could be the beginning of a real reset in Britain’s relationship with the Global South, to the benefit of everyone.