Written by John M. Rosenberg

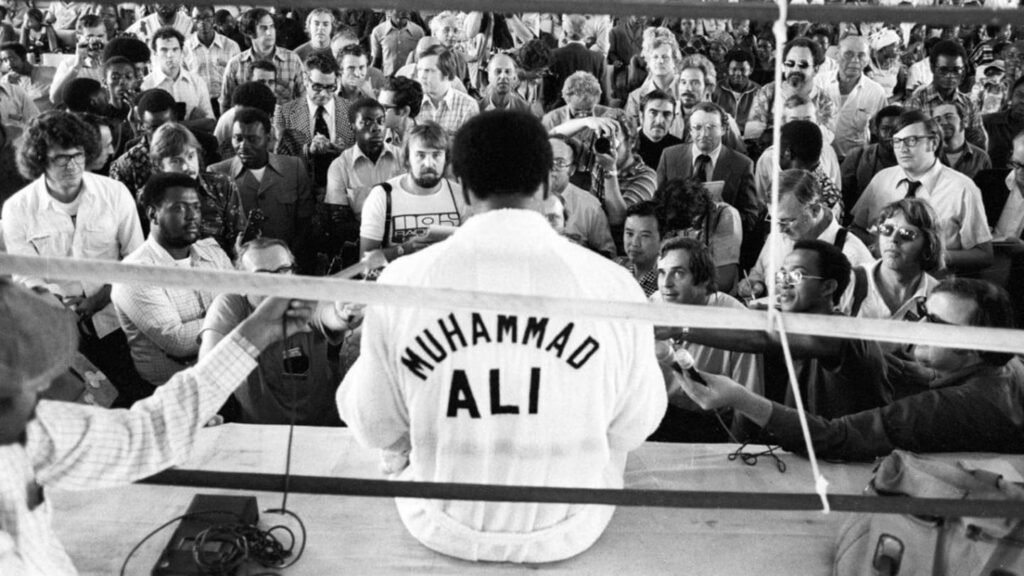

Fifty years ago, I closed the Rumble in the Jungle between heavyweight champion George Foreman and 4-1 underdog Muhammad Ali at the Rochester, Minnesota, Civic Center, now 11,300 miles away in Kinshasa, Zaire. He was the youngest ticket purchaser to watch the game via circuit satellite. Democratic Republic of the Congo. Moments after Foreman hit Ali’s five-punch combination on the canvas in an eight-round pirouette, I ran out of the arena and into the city, excitedly shouting to the indifferent traffic cops that Ali had won.

This battle not only provided the thrill of victory unlike anything I had ever experienced at a sporting event, but it also solidified the already budding bond between this Minnesota teenager and Africa. did.

Pre-match satellite broadcasts showed a stadium filled with Zairian dancers, dancing polyrhythmically as Mobutu Sese Seko, the glorious leader who dropped a $10 million purse to lure Kinshasa to an adrenaline-fueled match. He was shown praising the president on air. A giant paternalistic portrait of Mobutu, wearing his trademark leopard skin hat, loomed grandly in the arena below. Even from the other side of the world, the atmosphere was thick, piercing, and alluring.

Mobutu, known as America’s favorite dictator, was not the first to host a sporting event as a public relations smokescreen, but Rumble in the Jungle became Africa’s first global event.

In some ways, it’s a miracle that the battle even happened. The continent itself, much less Zaire, had no satellite technology or experience hosting an event of this scale. In addition, a black American boxing promoter in the form of a brilliant but slippery ex-con named Don King, whose only previous experience was organizing exhibition boxing matches in his hometown of Cleveland, was involved in a fight. I couldn’t imagine putting it together.

Today, it’s hard to imagine the status boxing held in the sporting world for the better part of a century. This world of sweet science has had several golden ages, the culmination of which was the era of Muhammad Ali, Joe Frazier and George Foreman in the ’60s and ’70s. It was a time when championship matches were held in places like Zaire, Malaysia, and the Philippines, and the title of World Heavyweight Champion lived up to its name.

For both Africans and Ali himself, the battle was seen as a return home. Through his grace, skill, and cunning, Ali truly became one with the African people.

Of course, it was more than this battle that fueled my love for the continent. For me, Africa offered something other than the front page headlines of the Cold War and Watergate.

As a child, I pored over the Collier’s Encyclopedia yearbooks that my parents paid dearly for for my older brothers. The early 1960s editions in particular captured my imagination, flashing with stories in which brand new nation-states emerge onto the world stage, one after another, like stars born in the molecular clouds of space. Each had a George Washington named Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyere, and Jomo Kenyata. I couldn’t help but wonder what all these places and people were so far from my American Midwest.

Half a century after the battle, Africa also gives me a sense of encouragement, and like Muhammad Ali, who was down 5-1 in Kinshasa, it is a story of overcoming the impossible, a can-do attitude. I’m proud of that. DD

Over the next decade, Africa will experience the greatest economic growth of any continent. That middle class is expanding. There is immense potential in the technology sector, with 17 African countries having more than 60 operational satellites in orbit by 2024, unlike the Rumble in the Jungle when there were no African-owned satellites. I’m putting it on.

To fully understand Africa in the 21st century, we need to understand radically different ways of thinking than in 1974. The time has come for Africa to take center stage on the world stage, and its people will no longer tolerate being told what to do by dictators or the outside world. In the aftermath of the Rumble in the Jungle, writer Norman Mailer wrote that Ali won the way he wanted, against a rope that no one, including Ali’s own manager, wanted him to do. I wrote that it was because I fought.

Like ants, Africa is also fighting against challenges in the way it sees fit. In Ali’s words: “Impossibility is not a fact. It is an opinion. Impossibility is not a declaration. It is courage. Impossibility is possibility. Impossibility is temporary. .impossible is nothing.”

John M. Rosenberg is the founder of Rossilne Group International and an expert on African issues.