[ad_1]

AU targets new mercenary brand in Africa

The draft treaty against mercenaryism is a welcome step, but it needs to include a strong monitoring committee and clear reporting lines.

Published on ISS Today on October 9, 2024

by

Musa Soumahoro

ISS Addis Ababa, African Peace and Security Governance Researcher

While exact figures are difficult to verify as mercenary activity is often shadowed, there has certainly been a resurgence in the use of hired soldiers in Africa over the past decade. Countries are increasingly using them to help address violent extremism and other internal conflicts.

Past mercenary experience in Africa has seen small groups of 50 to 500 people assigned to short-term, sporadic missions for each intervention. Currently, the number is steadily increasing.

In December 2020, Stephanie Williams, Acting Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General and Head of the UN Support Mission in Libya, reported that Libya alone has approximately 20,000 foreign troops or mercenaries stationed there. In 2022, an estimated 2,000 employed soldiers supported the Central African Republic (CAR) military. Mali had approximately 1,645 contractors as of April 2023, and the presence of mercenaries has also been reported in Mozambique, Sudan, and Burkina Faso.

The “private” status of contracted individuals or entities is increasingly questioned.

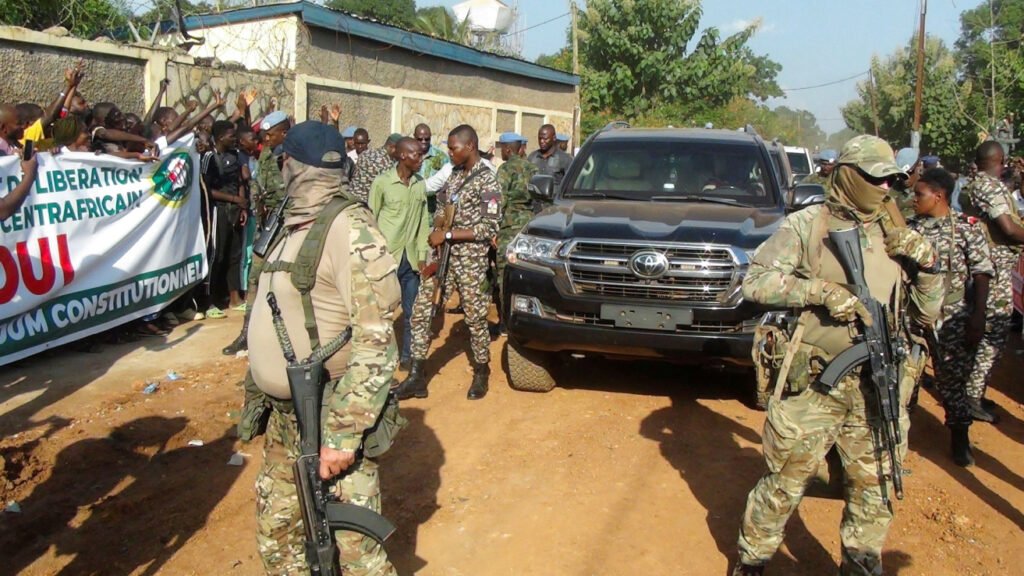

The inability of regional organizations to respond to security crises and the constraints facing institutions such as the African Standby Force have led to increased reliance on private military contractors. Their missions range from training and providing advice to troops in Burkina Faso and Niger to direct combat participation in Mali and Central Africa, where Russia’s Wagner Group (now Afrika Korps) is openly used.

Although these countries claim that these arrangements yield positive security outcomes, the recent killing of citizens by mercenaries in Mali has brought to light their disregard for human rights norms during their operations. is causing concern. In countries where mercenaries operate, particularly in northern Mali and the Central African Republic, brutal and indiscriminate use of force has resulted in significant civilian casualties.

The African Union’s Peace and Security Council (PSC) has repeatedly discussed this threat, stressing the urgent need to strengthen the 1977 Organization of African Unity Treaty for the Elimination of Mercenaryism in Africa. In December 2023, the PSC called for an expedited review of the treaty, and a draft is currently expected to be submitted.

The 1977 Convention expands the definition of mercenaries and their activities based on the realities of the time that led to its adoption. The report notes that external actors are using irregular contractors to remove political leaders who are seen as interfering with their interests. The treaty treats mercenaryism in Africa as an imported rather than an indigenous phenomenon.

The ongoing review is a key milestone in the AU’s efforts to tackle mercenaryism

Even as African civilian organizations such as Executive Outcomes emerged in the late 1980s and actively participated in conflicts in Sierra Leone and Angola, the 1977 Convention’s definitions of mercenary and mercenary activities were maintained. Provisions that focus on the private nature of mercenaries and hold contractors and employing organizations accountable remained fit for purpose until the late 2000s.

Subsequently, the tournament’s failure to anticipate state-owned or state-linked mercenaryism in Africa became a problem. The “private” status of individuals and organizations contracted to operate on the continent is increasingly being questioned. Some operate openly or under the indirect control of other countries, as in the case of Russian operators working for Afrika Korps (formerly Wagner). The best-known groups – Wagner, Convoy, and Redut – are associated with the Russian Ministry of Defense.

Africa also lacks a continental structure to provide oversight and help control mercenaryism. As a result, the AU’s follow-up on member states’ compliance with the 1977 Convention and its support for domesticating its provisions has been limited.

The PSC-inspired review produced a 40-article draft treaty, based on engagement with Member States, African civil society organizations, and international partners, and a policy outline on the impact of mercenary activities to silence the guns. The draft treaty stipulates the establishment of a monitoring committee on mercenaryism, and expects member states and civil society to play a role in supporting the committee.

Review committee should consider provisions to monitor human rights violations by mercenaries

The draft treaty also provides for monitoring and reporting by Member States to ensure effective dissemination within the country. And the definition of mercenaries and their activities have been expanded to suit the continent’s current realities.

The ongoing review is an important milestone in the AU’s efforts to tackle mercenaryism. But success will depend on establishing a strong oversight committee and making clear how it will work with and report to the PSC. Regular briefings to the Council should be included in the PSC’s annual program to ensure that mercenaryism is controlled at the highest decision-making levels of the AU.

When the Review Committee finalizes the draft treaty, it will need to consider provisions to monitor human rights violations by mercenaries operating in conflict zones. These human rights violations should be referred to existing judicial frameworks, such as the African Court of Human Rights, to ensure accountability for violations against civilians.

This article was first published by ISS PSC Reports.

Exclusive rights to republish ISS Today articles have been granted to South Africa’s Daily Maverick and Nigeria’s Premium Times. If you would like to republish an article in media based outside of South Africa and Nigeria, or if you have any questions about our republication policy, please contact us by email.