The Komati factory was the main employment provider for this small town. The quiet streets are dotted with lumps of coal, and some houses are now empty as workers from other states have returned home without jobs.

By Zama Luthuli/AFP, Middelburg, South Africa

The cold corridor of South Africa’s Komati coal-fired power plant, which was touted as a pioneering project in the world’s green energy transition, has been quiet since it closed in 2022.

Two years later, plans to repurpose the nation’s oldest coal-fired power plant have done little to help in the process of offering warnings and lessons to countries seeking to reduce their dependence on fossil fuels and switch to renewable energy. There wasn’t.

Jobs have been lost, wind and solar construction has not yet begun, and only a few small green projects are underway.

Photo: AFP

“We can’t build anything. We can’t remove anything from the site,” said acting general manager Teben Pillay of the 63-year-old factory in Mpumalanga’s smog-choked coal belt. spoke.

He said poor planning and delays in paperwork to approve the plant’s complete decommissioning were the main reasons for the shutdown.

“It should have been done earlier. So we would consider it not a success,” he said.

Before switching off in October 2022, the plant delivered 121 megawatts (MW) to South Africa's chronically undersupplied and unstable power grid. The transition plan, which received US$497 million in funding from the World Bank, envisages generation of 150 MW from solar power and 70 MW from wind power, with 150 MW of battery storage capacity.

Workers will be retrained and the factory’s infrastructure, including giant cooling towers, will be reused.

But much of that is still a long way off.

Samantha Graham, South Africa’s deputy energy and power minister, said: “They have effectively shut down coal-fired power plants and left it up to the people to deal with the consequences.”

80% of South Africa’s electricity comes from coal, making the country one of the top 12 greenhouse gas emitters in the world. Coal is also the basis of the economy, employing approximately 90,000 people. South Africa is the first country to enter into a Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP) with international funders to move away from dirty power generation, with a total investment of US$13.6 billion already in place, according to Neil Cole, president of the South African Presidential JETP Committee. It is said that it has received subsidies and loans.

The Komati coal-fired power plant is the first coal-fired power plant scheduled to be decommissioned, with five of the remaining 14 coal-fired power plants scheduled to be decommissioned by 2030. Eskom, the state-run energy company that owns the power plant, said the Komati coal-fired power plant directly employed 393 people.

Only 162 people remain on the site as others have volunteered to transfer or accepted payments. The mill was the main source of employment in this small town whose quiet streets were dotted with coal blocks. Several homes now stand vacant as workers from other states lose their jobs and head home.

Sizwe Shandu, 35, who had been contracted as a boiler maker at the factory since 2008, said: “The end of the job was a huge trauma for us as a community.”

The closure was unexpected and left families scrambling to make ends meet, he said.

South Africa’s unemployment rate is over 33 percent, and Shandu now relies on government social grants to buy food and electricity.

Mr Pillay acknowledged that many people in Komati town had an “unhappy view” of the transition.

One mistake, he said, was that coal jobs were closed before new jobs were created.

Townspeople didn’t always have the skills needed for new jobs. Eskom said it plans to eventually create 363 permanent jobs and 2,733 temporary jobs in Komati.

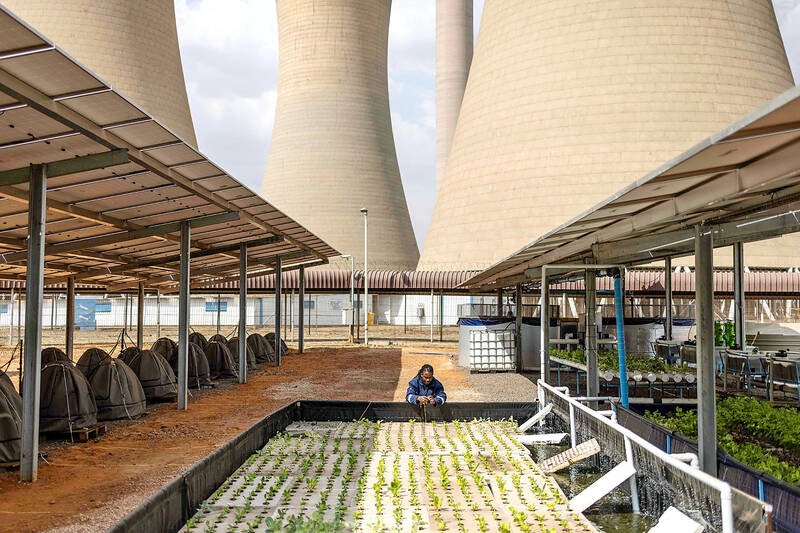

One of the ongoing environmental projects combines fish farming alongside a vegetable garden supported by solar panels.

Of the 21 people planned, seven people have been trained to work on the aquaponics project, including 37-year-old Bheki Nkabinde.

“Eskom has helped me a lot in terms of getting this opportunity, because I can earn an income and support my family,” Nkabinde says as she walks among spinach, tomatoes, parsley and green onions. spoke.

The facility processes invasive plants into pellets to replace coal and assembles mobile micro-power grids affixed to containers. A coal milling workshop has been transformed into a welding training room.

Mr Pillay said the failure at Komati could serve as a lesson for other coal-fired power plants targeted for shutdown.

For example, some companies are currently planning to launch green energy projects in parallel with phasing out emissions.

But the country “is not going to be forced to make decisions about how fast or how slowly to make a just energy transition based on international expectations,” Graham said.

She said South Africa’s renewable energy share was 7%, up from 1% a decade ago.

Eskom continues to mine and export coal and estimates it still has around 200 years’ worth of coal underground.

The goal is to have a “sustainable, stable and good energy mix,” Graham said.

Since South Africa’s JETP was announced, Indonesia, Vietnam and Senegal have also entered into similar agreements, but little progress has been made towards actually closing coal-fired power plants under the mechanism.

Among the criticisms is that they primarily offer market-rate loan terms, increasing the threat of debt repayment problems for recipients.