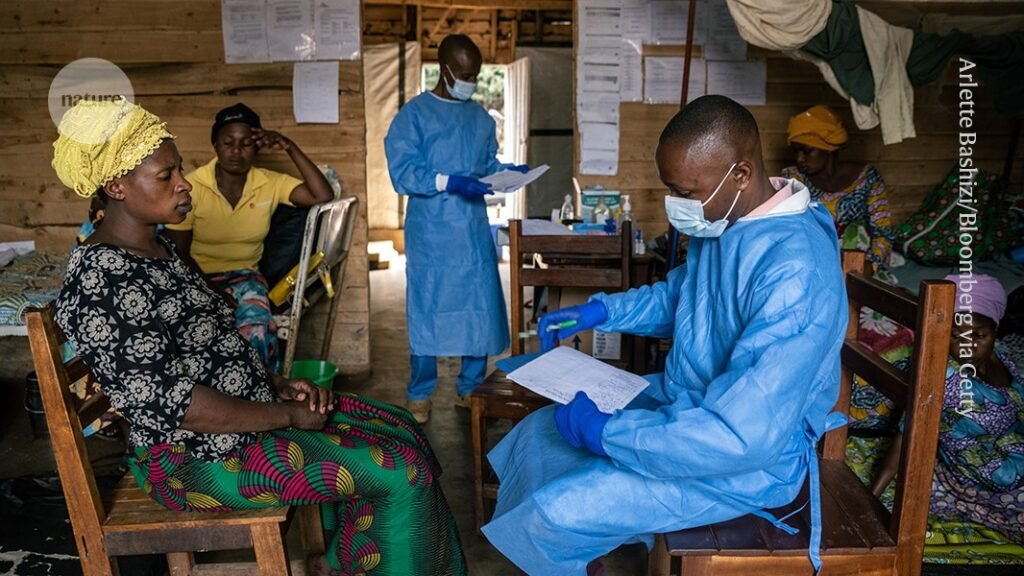

A doctor meets with a patient being treated for mpox at a hospital in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Credit: Arlette Bashizi/Bloomberg via Getty

Mpox spread to 15 African countries in 2024, but six of those countries have no cases of the disease, and health authorities have so far been able to contain the continent’s deadliest Mpox surge. I’m trying to do my best. But they finally have a new and helpful tool: a vaccine, which has not been available in Africa until now, even though mpox was detected on the continent decades ago.

Nikeise Ndembi, a virologist at the African Centers for Disease Control and Prevention in Addis Ababa, said the MPOX vaccine, which is used in rich countries such as Germany and the United States, will remain safe in Africa during a global outbreak of the disease in 2022. He says it didn’t happen. But doses began arriving this year after the World Health Organization declared MPX a global public health emergency for the second time in history.

On September 17, Rwandan health authorities began administering the jab to people at high risk of infection. The Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC), the country hardest hit by the pandemic in Africa, will take similar measures on October 5th. And Nigeria plans to begin its own vaccination drive within the next two weeks.

Virologist Nikeise Ndembi is coordinating the mpox response at the African Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Credit: Russian Look (via ZUMA Press)

These moves come as African countries report more than 31,400 suspected mpox infections and 844 deaths in 2024. They also occur as a new strain of the virus that causes mpox, called clade Ib, spreads through densely populated areas and partly through sexual contact. This means that it can be transmitted efficiently from person to person.

It is still unclear how effective the vaccines being distributed are against clade I viruses. Vaccines helped during the pandemic two years ago, but that crisis was caused by a different strain called clade IIb. Still, many scientists emphasize that they are safe and expect them to work.

Here, Ndembi, who is coordinating Africa CDC’s mpox response, talks about how health officials plan to distribute the new doses and the challenges they will face.

Are the doses you are receiving the ones expected as part of an equitable global response during the 2022 global outbreak?

we are doing much better. Approximately 275,000 doses of the vaccine are currently on hand and have already been shipped to countries for administration. In the 2022 pandemic, not a single dose of vaccine was administered.

Adding up the pledges and the doses already delivered, approximately 6.1 million doses will be delivered. But you cannot take the pledge and get vaccinated. The 10,000 vaccine doses Nigeria received in 2024 were actually pledged for 2022. So you can see the disparity. But it’s incredible that 6.1 million doses have now been promised. Now we need to see them come true.

We are looking at vaccinating 10 million people (in Africa), but that number may need to reach 14 or 15 million.

Until more doses arrive, how will countries prioritize who gets vaccinated first?

This is not a vaccination campaign. The message behind the word “campaign” suggests that anyone can participate. But we’re going to be very targeted. We want to reach specific groups, but this approach can lead to problems within the community without proper communication about who is most at risk of infection and why we are prioritizing certain groups. We assume that the problem may occur. We know that many people are looking forward to the vaccine. Vaccines are a silver bullet for many people. The stigma associated with mpox (which causes visible fluid-filled lesions, among other symptoms) means everyone wants to get vaccinated.

As an example of prioritizing certain groups, Rwanda has started vaccinations and is highly targeting female sex workers and high-risk cross-border traders, truck drivers and health workers. I’m doing it. We also use a “ring vaccination” approach. Identify the close contacts of the infected person and ensure that they are vaccinated first.

DRC is battling an outbreak of multiple virus strains from clade Ib and clade Ia. Clade Ia is usually spread to people through infected animals. Will it affect how vaccines are distributed?

Let’s start with the hotspot. The most affected states will be selected in the first block, after which we will move on to other regions.

When it comes to the different subtypes of viruses, let’s be clear: viruses don’t know boundaries. We need to move away from the idea that (mpox) subtypes can be restricted to geographic areas. Kinshasa (capital of the Democratic Republic of the Congo) has both clades Ia and Ib.

We’re not going to say, “Let’s start vaccinating in the clade Ib region and then go to the Ia region.” That’s too complicated.

Kinshasa is the entry and exit point for almost all travelers passing through the region. There is certainly concern, as infections there can easily be carried anywhere in the world.

How will you monitor the effectiveness of the vaccine as people receive it?

We already have a team in Rwanda working to monitor adverse events and ensure the vaccine is effective over the long term. They will study immunogenicity, safety and efficacy, as well as durability (how long the vaccine remains effective).

(Editor’s note: A clinical trial tested more than 1,500 people aged 10 and older with confirmed mpox infections in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda, and Nigeria to determine whether the vaccine could reduce the risk of developing the disease in their contacts or the severity of the disease.) The aim is to understand whether it is possible to alleviate their disease.

What does success look like?

In the DRC, we are dealing with a country of 100 million people. We’re talking about over 30,000 suspected cases, but how many people will be able to get tested? Currently, about 40% of suspected cases are tested; Approximately 60% of them were found to be positive. That means we’re not testing as much, and people are traveling with the virus without knowing they’re infected.

An epidemic can be brought under control when new infections stop coming from contacts of people known to be infected. Vaccines are aimed at breaking these chains of infection, so that’s what we want.

But vaccination is just one tool in the response. Risk communication, community engagement, and laboratories (infrastructure) are equally important.

What was the biggest challenge in controlling this outbreak?

First, mpox is endemic in some parts of Africa. There are provinces within the DRC where cases have been reported for decades. There are not enough tools to quickly detect viruses. For HIV, the test takes less than 5 minutes and results are 99% accurate. It would be great if we could test for it (as is the case with HIV).

Another issue is drugs. Tecobirimat, an antiviral drug against mpox, was effective against clade II during the 2022 pandemic, but has been shown to be less effective in Africans in the Democratic Republic of Congo. And finally, there aren’t enough vaccines. This is a very strong case for local manufacturing across the continent. We need to start producing diagnostic kits, medicines and even vaccines here.