As you head south in the United States, the clichés disappear and things start to become more Biblical. As you continue into the Deep South, things get surreal. It is a country that fears God, but beyond that there is a place where even God begins to become distorted. Chicago may have been the place where American music was electrified (with the Great Migration of some 6 million black Americans northward), Detroit may have been the place where it was perfected on the production line, California While it may have developed under the sun and neon lights of New York, the true musical crucible for American popular music was the Deep South. Congo Square, Sun Records, Grand Old Opry, Stax. Jazz, rock and roll, country, soul.

Now they are all easily categorized and institutionalized, but their confluence (gospel and blues from African American churches and juke joints, Scots-Irish folk from Appalachia, Creole zydeco and (Cajun faiz de do, Southern Gothic, etc.) further enriched the Delta landscape. It’s more vivid and fantastic than is often known. The cast of characters is unique – Jelly Roll Morton, Memphis Minnie, Clifton Chenier, Empress of the Blues Bessie Smith, Dr. John, Skip James, Professor Longhair, Johnny Ace and the Beale Streeters, Howlin’ Wolf, Son House, The Big Oh! Murderer, Baron Samedi, whoever bought Robert Johnson’s soul or poisoned his whisky. And while the place may not be what it once was (where is it?), there’s more than a hint of the strange chemistry from which culture is born: Crystal Shrine Ghetto, Marie Laveau’s Voodoo House, the ruins of Jazzland, the cave where Knickerjack Johnny Cash once went to die, and Graceland, home of Ludwig, the Mad King of the Deep South.

William Eggleston belonged to this place. The Memphis-born drunkard and hard drinker, though aristocratic (in all its shades) by birth, was one of the cast and one of its greatest ethnographers. He was also a revolutionary in photography, changing professions just as his friend Henri Cartier-Bresson did with his “Decisive Moment”. At first, Eggleston’s “Democratic Forest” appears to be the polar opposite of Cartier-Bresson, whose perfectly timed shots made street scenes and people look grand, at least for a fleeting moment. By comparison, Eggleston’s photographs seemed chaotic and insignificant.

These are color, a medium despised by “serious” photographers, erasing, for example, the amazing history of autochrome and the fact that life cannot be lived in black and white. But both photographers were advocates of recalibrating how we see the world. For Eggleston, nothing was ordinary if you looked at it the right way, or the “wrong” way. Worldliness was simply in the eye of the beholder. As exemplified by “The Red Ceiling,” he has shown us a world that we had previously ignored and stories that no one had imagined. Filmed in Greenwood, Mississippi in 1973, the song became famous as a Radio City cover by Memphis native Big Star. It’s just a light bulb and a wire in a room somewhere, but it’s still strangely charged, menacing, intense, and mysterious. You don’t see anything, but when you look back you feel it.

Eggleston presented the invisible and familiar from an angle that revealed the everyday as a mere illusion of self-indulgence. By his own admission, he was not the first to make such remarks, naming Lee Friedlander and Gary Winogrand and lamenting that their pioneers were not pursued. It took Eggleston a while to make it stick, to realize that the remnants and gems of Americana weren’t all that far apart, even though so much was being ignored. “I’m fighting the obvious,” Eggleston told an interviewer, which was a noble declaration given the falsehoods and snobbery that masquerade or hide behind the obvious.

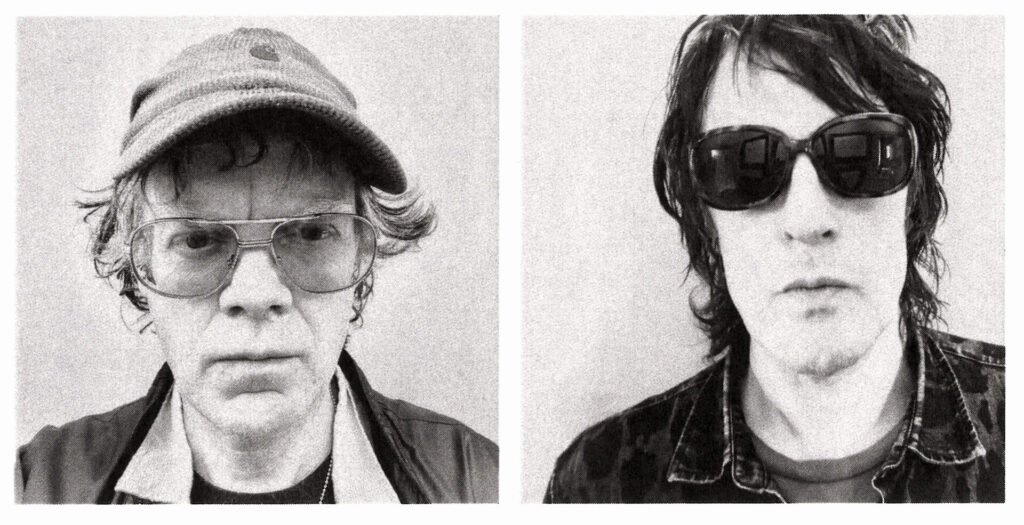

Stranded In Canton is Eggleston’s 1974 documentary about the Deep South and its inhabitants, most of whom are his friends, co-conspirators, family members, or fellow prodigals. There are a lot of weirdos, sociopaths, and so-called “characters” that you meet as you live a certain kind of life. Judging by the monologues and dialogue on this soundtrack, the scenario feels like it’s going to explode within seconds (the atmosphere is, as Richard Williams puts it, “Hogarth on Beale Street”). Madness, danger, divine inspiration, or villainy never seems far away in what is ostensibly a highly eccentric and exceptional home movie, with guns, nerds, and quaaludes. I can see why this movie was beloved by later directors like Harmony Korine and Gus Van Sant. And why did J. Spaceman and Spiritualized’s John Coxon, at the invitation of artist Doug Aitken, decide to create the film’s soundtrack at the Barbican in 2015? Fat Possum have released an album that will be followed by a series of live performances of the new score. The advertising emphasizes that these are not typical Spiritualized shows. After all, we’re not in Kansas anymore.

There is little trace of Space Station Spectre or Spiritualized Ocean Sigh here. “I’m Stranded in Canton” initially has a Spaceman 3 feel to it, with hints of the “cosmic American music” championed by Gram Parsons. But instead of floating into a big, Lanois-esque sky, it descends into a wild, claustrophobic Deep South night, the music weaving threads among the raucous voices. Rather than the psychedelia its title suggests, “Last Week I Traveled” is a gripping, jarring bayou blues, while the taut “It’s Not Gospel” is a bit theatrical. However, we meandered through the hot line.

The gentler moments are as much country-tinged as they are indebted to the Velvet Underground. “What Train Blues,” “Back Up William,” and “Everybody in Their Life at One Time at a Time” include references to Robert Johnson’s “Love in Vain.” It has a vulgar, relaxed vibe, similar to the Stones version. Throughout, you can feel a sense of distance and resonance that transcends the Atlantic Ocean. It’s not so much about authenticity or kitsch as it is Americana as an alien broadcast spread across the globe, striking something deep in the souls of distant listeners, only to reappear in wonderful, mutated forms. “I don’t know what I can possible do,” for example, threatens to devolve into speed-freak rockabilly, but instead adopts a slow, JAMC-like groove. “Love for the ask,” on the other hand, is more of a swamp than a wall of sound. of feedback.

There are many climaxes throughout the album, but the clear clean sound of “Credits roll” is the only one that gives a sense of freedom. This is the microcosmic story of contemporary music: no matter what music is sent out into the world from this noisy, anti-establishment southeastern United States, the echoes that return are transformed in the process. The residents may be stranded, but their howls, rants and laughter are beyond their wildest imaginations.

Part improvisation, part composition, the music for William Eggleston’s Stranded in Canton is truly a journey, with circular arguments, declarations of justice, and barrooms stolen from the film amid layers of noise. It’s a spiral journey with recurring motifs such as piano and blown harmonica. Performed by the duo’s trance-paced guitar arpeggios, feedback drones, and rattlesnake acoustics. Music is sleep to the other side of the American dream. Is it totally fun? Give me a nightmare that isn’t perfect, but definitely not convincing.